Scientific illustrations transport us to the macrocosms and microcosms that

surround us with the myriad colours and forms of the flora and fauna endemic to our rivers,

forests and seas. In contrast to images that can transport us to a dream-like world of

imagination and fantasy, these illustrations need to be studied because their interpretation

calls for a certain specific knowledge of the sciences.

Nevertheless, the power of art decodifies and transforms technical information

into images that can awaken the observer’s curiosity about themes of science and nature,

making even a layman astonished by the beauty of the creatures that inhabit the planet.

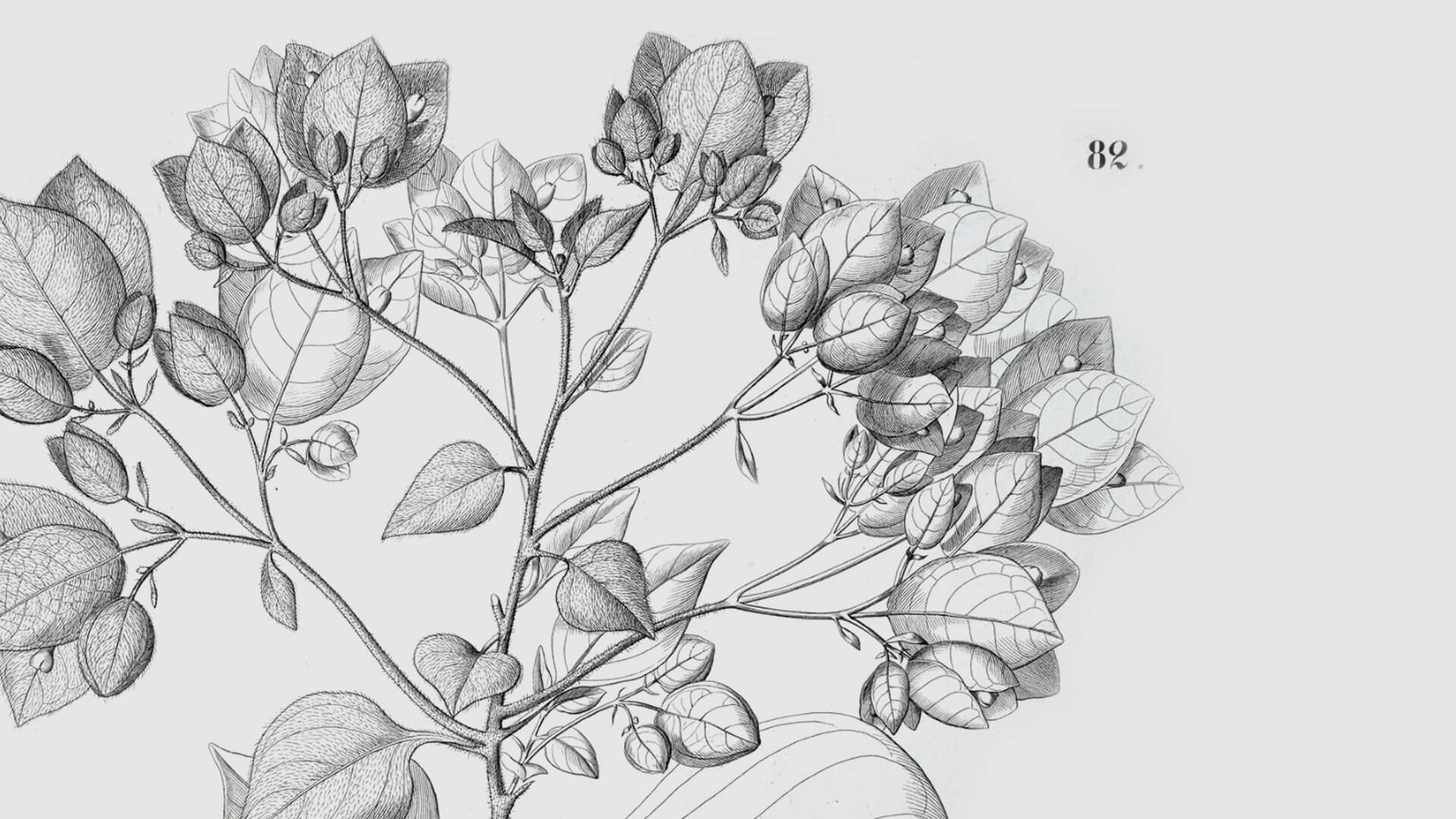

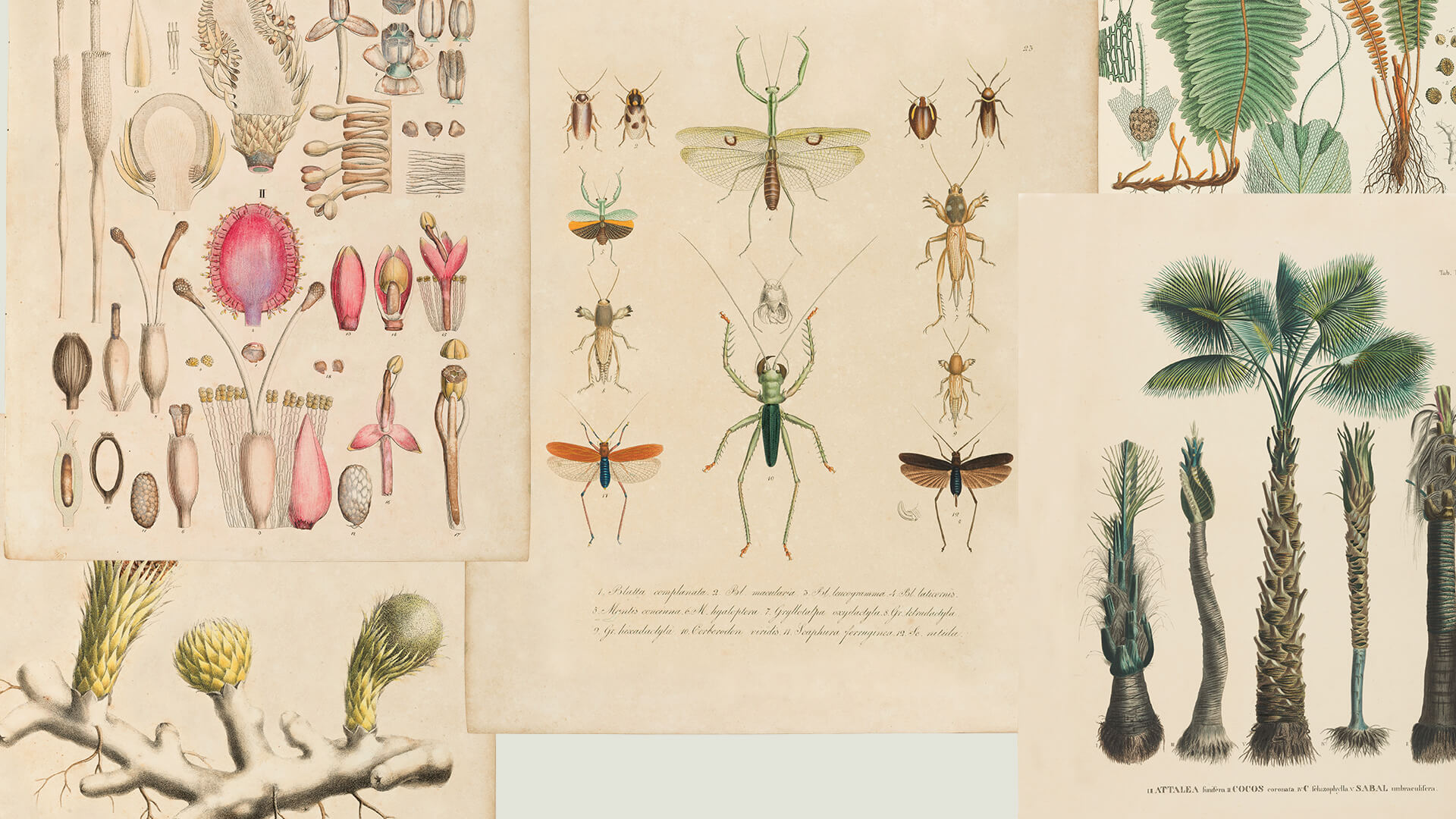

The production of countless anthologies of natural history illustrations,

especially in the 19th century, arose with the advent of engraving, which emerged at the

height of the Renaissance, in the 15th century.

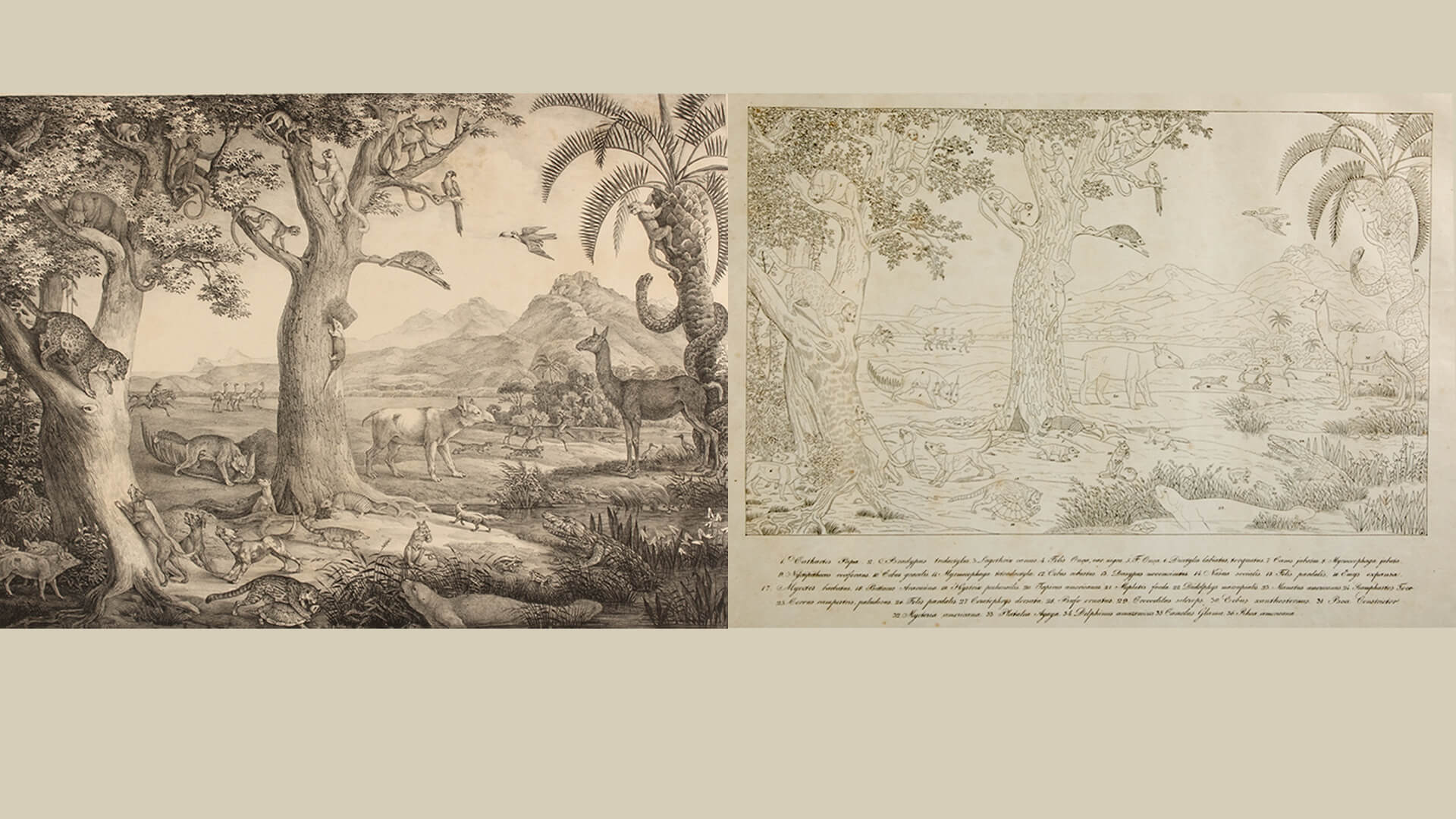

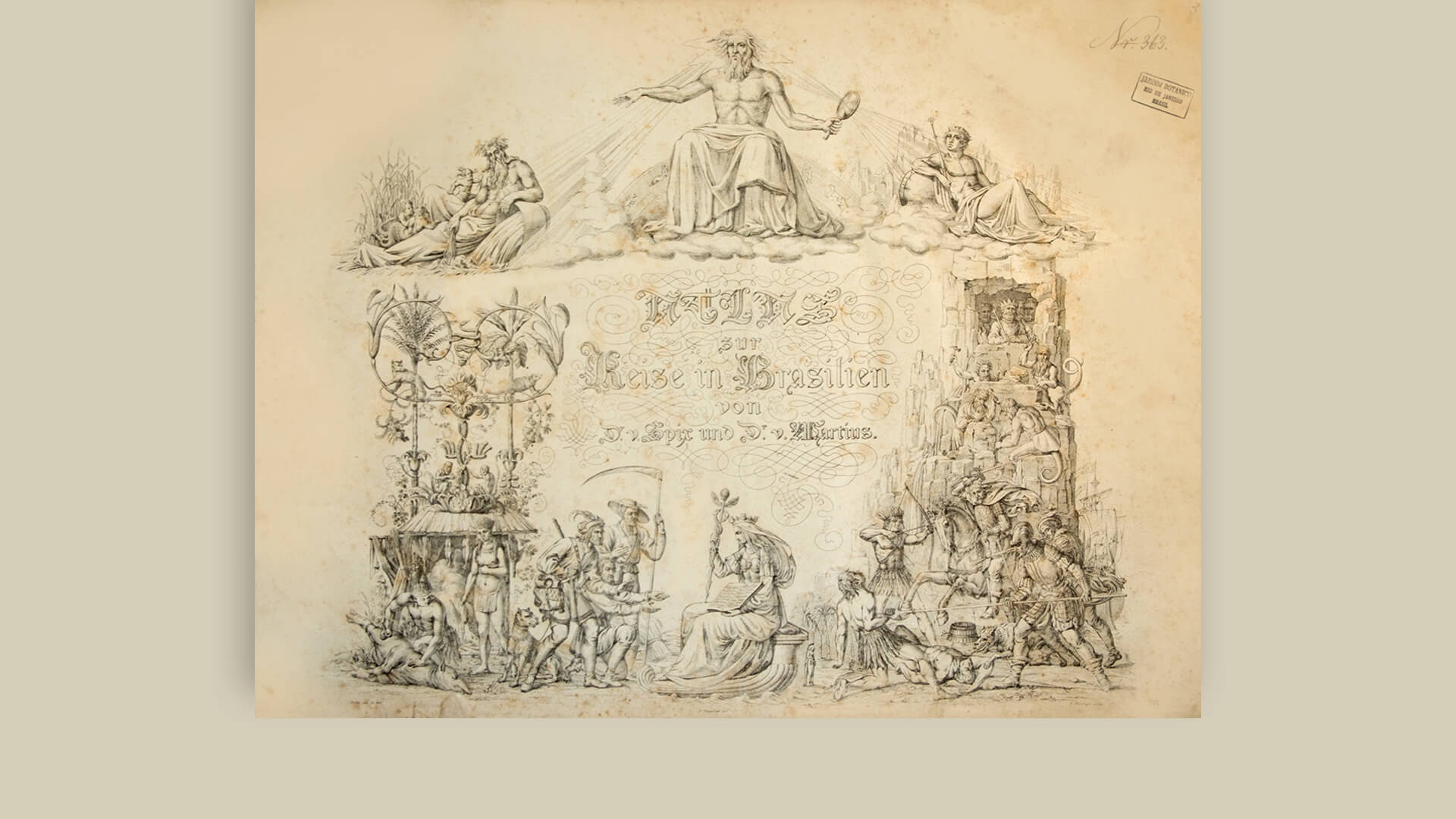

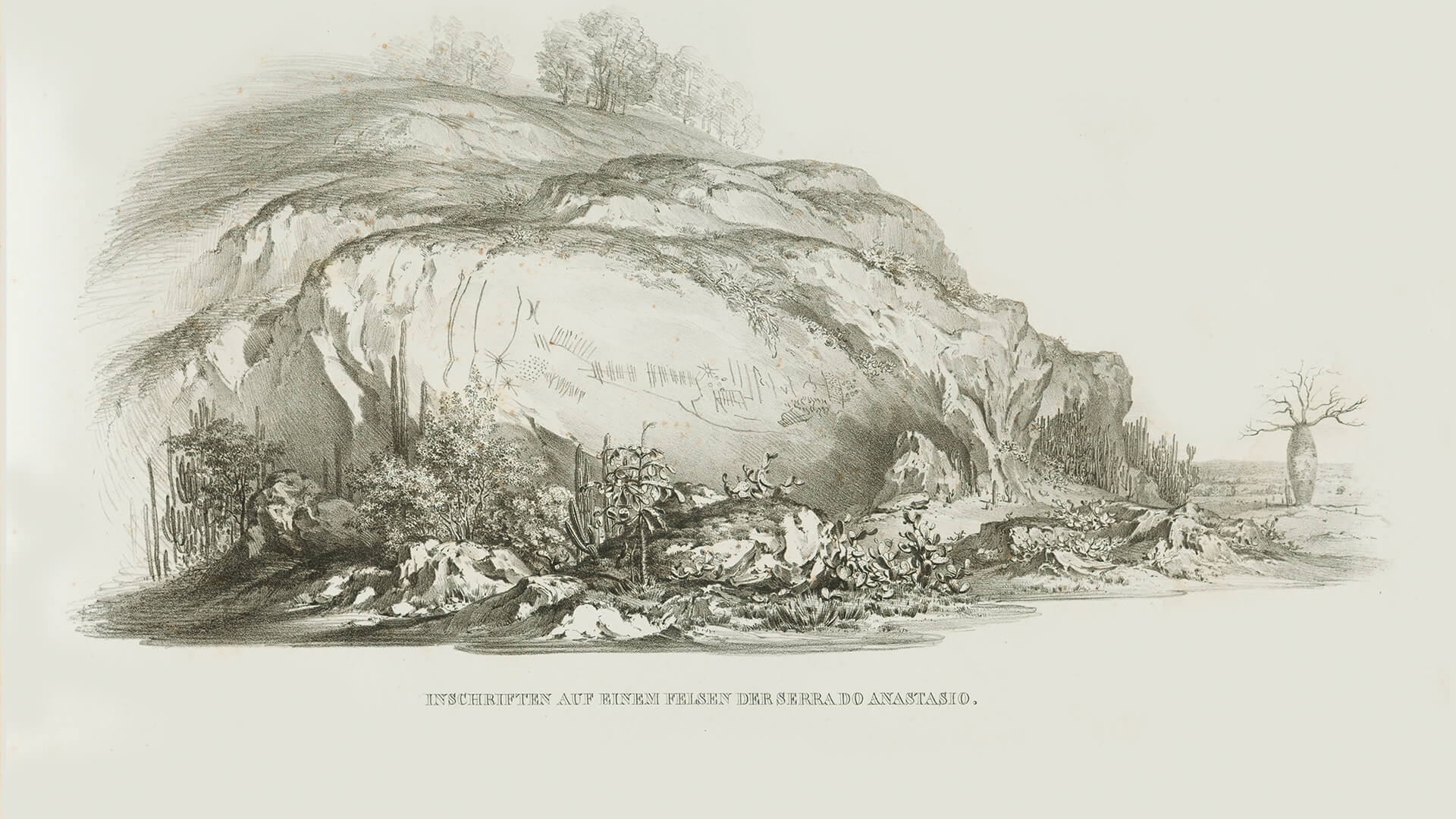

All of the works of Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius and Johann Baptist von

Spix are accompanied by original engravings and form an integral part of the movement in

favour of the dissemination and expansion of knowledge. Realistic and expressive drawings of

nature seen by Martius and Spix were reproduced in lithography or engraving on metal, being

hand-coloured or printed in colour, in prol of the dissemination of science.

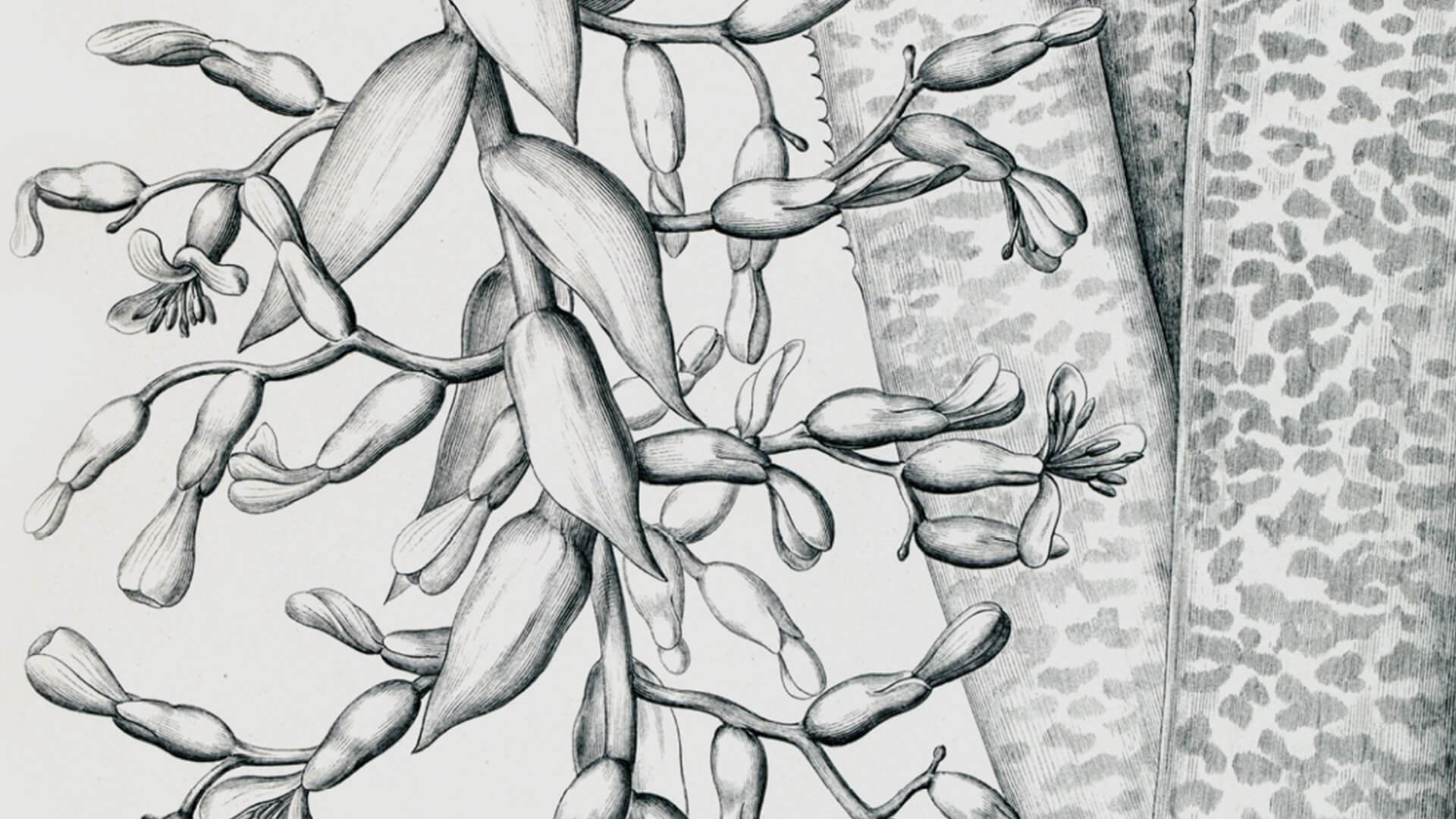

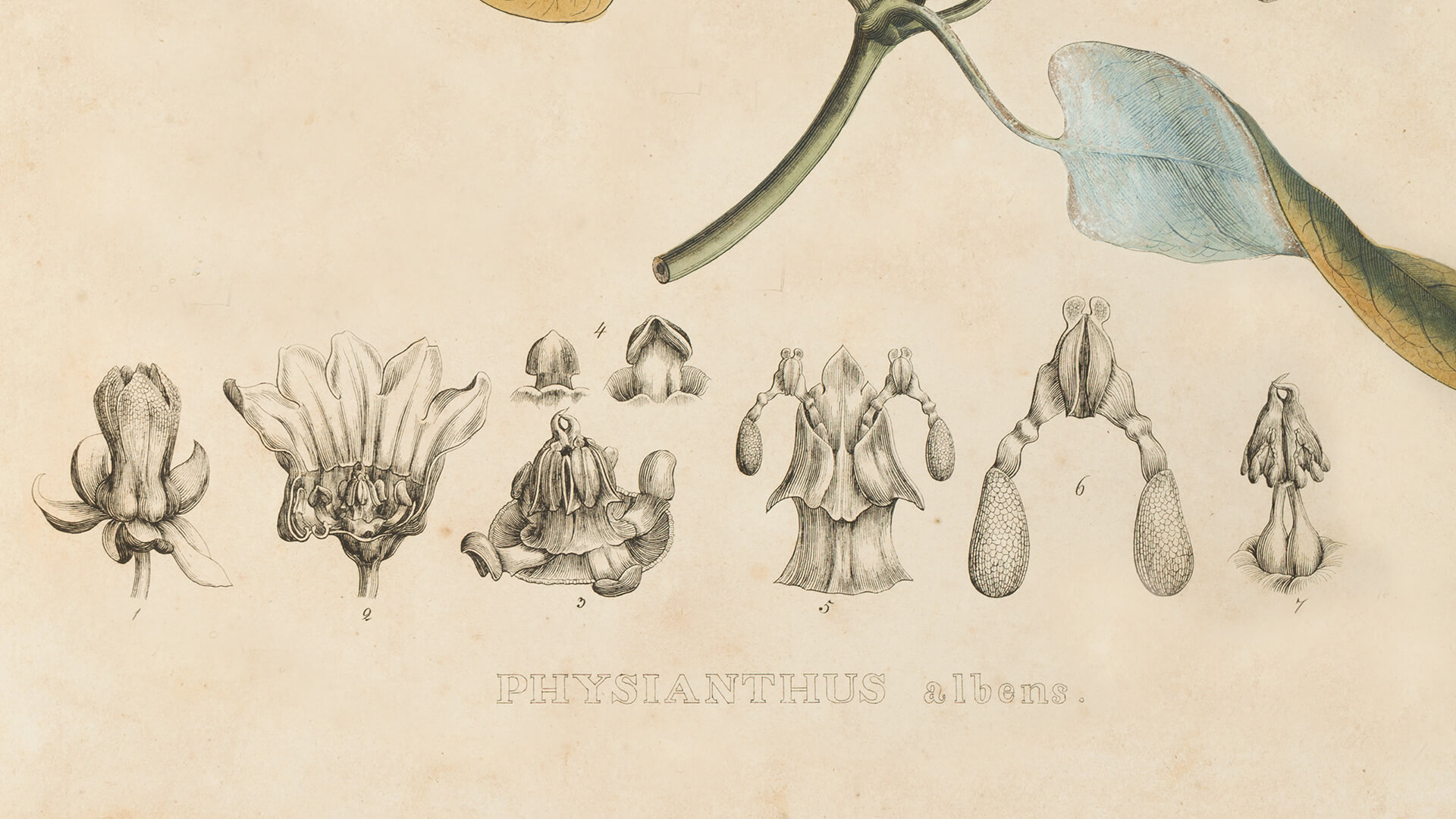

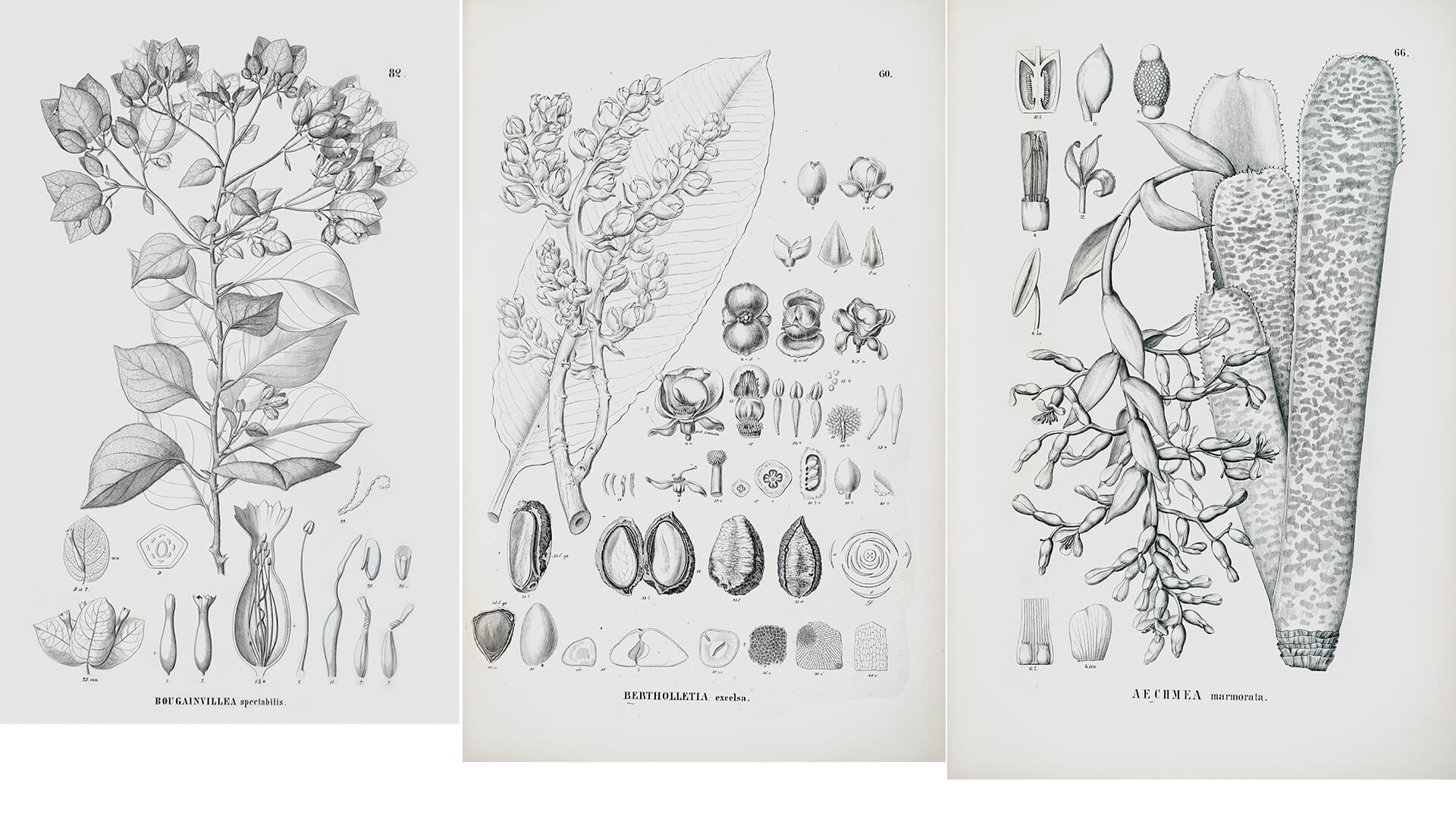

The illustrators of Natural History play an important role in the recording

and dissemination of themes relating to nature, especially in the representation of the

aspects of different landscapes and the diagnostic characters of species. In this context,

we can note that, with the advent of the new system of classification of the beings of

nature developed by Carl von Linné (1707-1778), scientific plates started to include

internal and external morphological characters, became richer, more detailed and

consequently more complex. This enabled comparison and more accurate classificatory

diagnosis, which called for technical mastery and refinement of the designers’ technique

under the supervision of the researchers.

The engravings of the works produced by Martius e Spix were made at different

times. Firstly, the process included the collection of physiognomic impressions, records in

situ by innumerable artists and by the naturalists themselves, with field notes and

sketches.

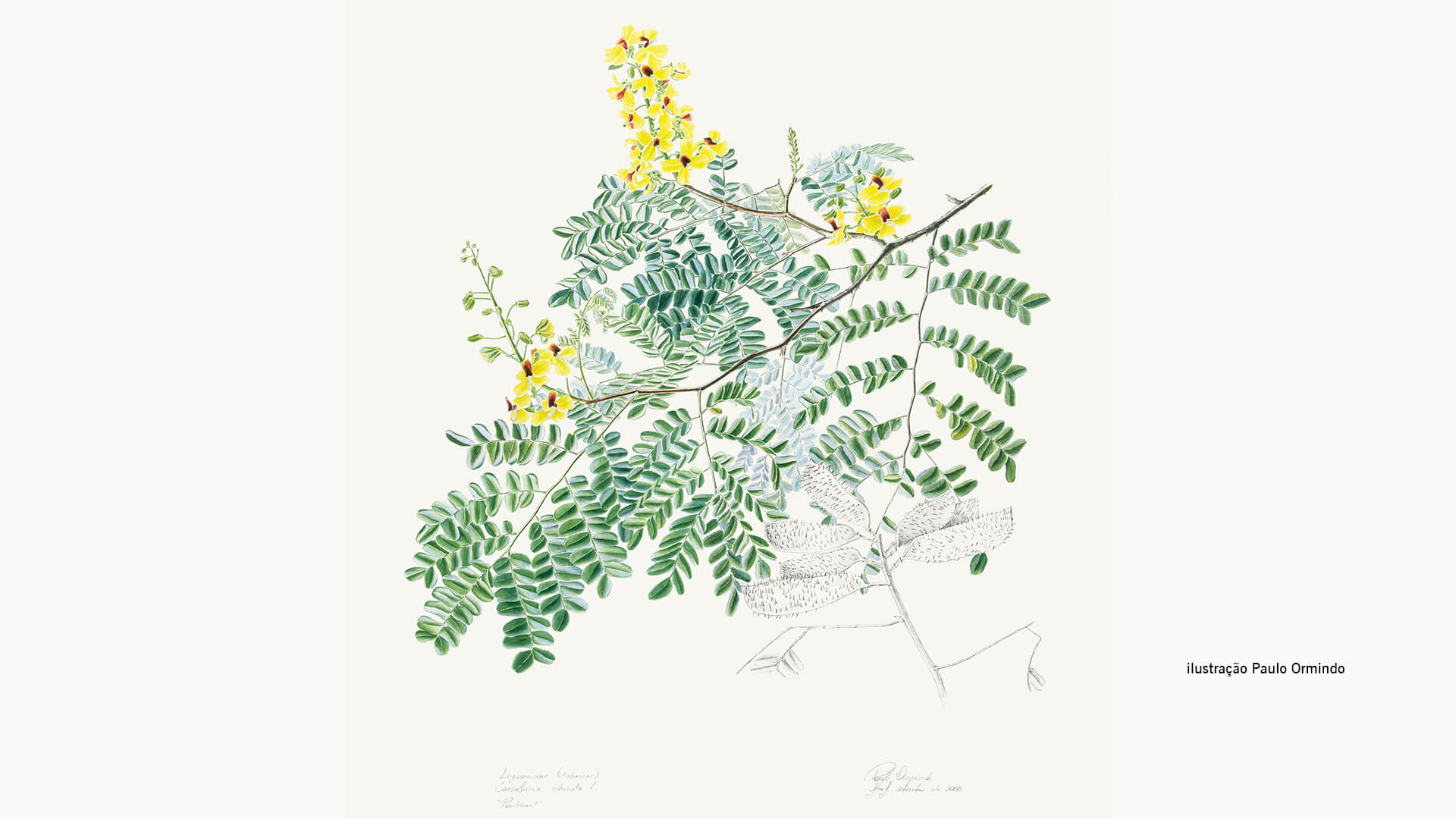

Today, scientific illustration, coupled with artistic treatment, continues to

play a predominant role in taxonomic studies for it is still the most effective way of

highlighting the differences that enable identification of plants and animals.

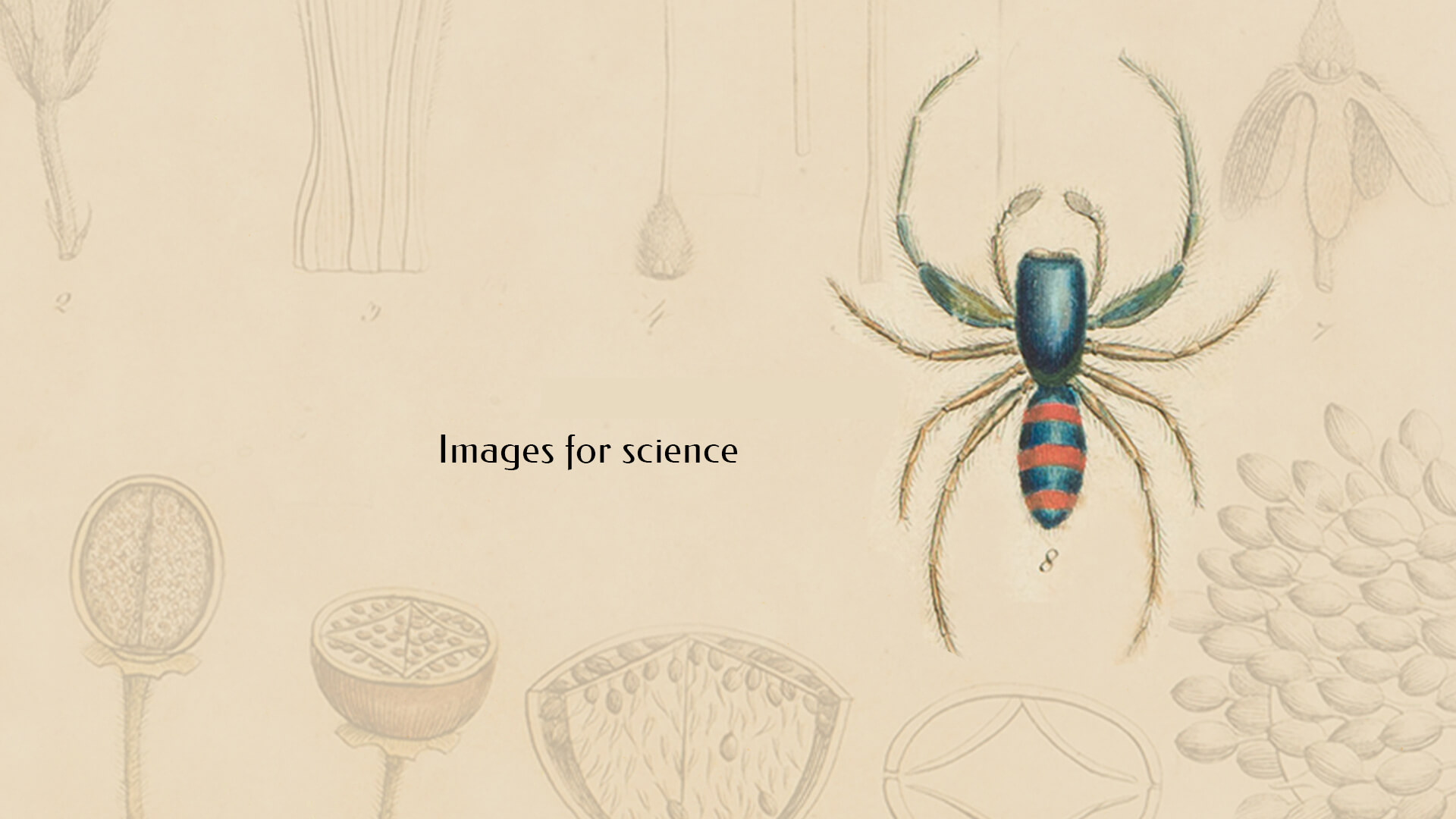

Images for science, not just in the works of Martius and Spix, are concerned

with the search for verisimilitude and realism in their elements. They invite us to

understand that scientific illustration reflects more than we can see, more than we can

understand and think, because it goes beyond. It sees both inside and outside.

It reflects the existence of a being, which can be beyond our reach, at risk or on the brink

of extinction. However, here it is displayed in its plenitude and fulfils its role of

representing its elements in a distinct way, enabling us to dream of having the same clarity

and permanence in our very natures, above all, preserved and intact.